When Courts Question Their Own: The Justice Jahangiri Case

Something unusual is happening in Pakistan’s judiciary this week. The Islamabad High Court is preparing to hear a case that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago—a petition challenging the eligibility of one of its own judges to sit on the bench.

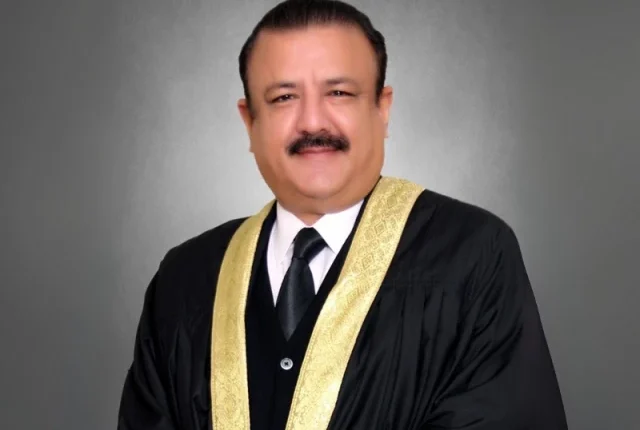

Justice Tariq Jahangiri, a sitting member of the Islamabad High Court, faces allegations that his academic credentials don’t meet constitutional requirements. The petition claims he holds an invalid degree, raising questions about whether he should have been appointed in the first place.

This isn’t your typical courtroom drama. We’re watching the judicial system turn its scrutiny inward, applying the same legal tools once used to remove prime ministers and parliamentarians to question the qualifications of a high court judge.

The Weapon That Changed Pakistan’s Politics

To understand why this case matters, you need to know about quo warranto. It’s a Latin legal term that essentially means “by what authority?” The petition asks a simple but powerful question: what gives someone the right to hold a particular office?

Pakistan’s superior courts used quo warranto extensively after 2009, when judges were restored following the lawyers’ movement. The Supreme Court didn’t just interpret laws during those years—it actively shaped the political landscape by removing people from office.

Lawmakers fell one by one. Prime ministers were disqualified. Heads of accountability institutions were removed. Civil servants lost their positions. The courts wielded Article 184(3) of the Constitution like a sword cutting through the political establishment.

The Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz and Pakistan Peoples Party bore the brunt of these judicial interventions. Senior lawyers now acknowledge that while some removals addressed genuine concerns, the overall effect weakened Parliament as an institution.

The Tool Turns Inward

Now that same legal mechanism is being tested against the judiciary itself. A division bench headed by Chief Justice Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar declared the petition against Justice Jahangiri maintainable last week. The court issued a notice to its own colleague, setting Monday as the hearing date.

Justice Jahangiri is expected to appear before his fellow judges to defend his qualifications. Imagine the dynamics of that courtroom. Colleagues who sit together on benches and collaborate on judgments will now evaluate whether one of their own deserves to be there.

The petitioner, Mian Daud, argues that Justice Jahangiri’s educational credentials don’t meet the constitutional standard. Barrister Zafarullah, serving as amicus curiae, has endorsed this argument. He contends that eligibility for high court appointment can be scrutinized through quo warranto.

Constitutional Requirements Under Question

Article 193 of the Constitution sets clear requirements for high court judges. They must have been licensed to practice law for at least ten years. It sounds straightforward, but there’s a complication. To get that license, you need a recognized law degree. If the degree is invalid, does that make the entire license questionable?

Some lawyers argue this issue belongs with bar councils, not courts. Bar councils regulate who can practice law, verify educational credentials, and issue licenses. If there’s doubt about someone’s degree, shouldn’t the Bar Council investigate?

The counterargument is that constitutional eligibility for judicial office goes beyond bar council jurisdiction. A bar council might decide someone shouldn’t practice law, but only courts can determine if someone meets constitutional requirements for judicial appointment.

The Immunity Problem Nobody Can Ignore

Here’s where things get complicated. The Supreme Court recently issued a detailed judgment stating that judges of superior courts enjoy immunity from writs and actions by judges of the same court. Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail’s eleven-page order explained that constitutional immunity exists to protect judicial independence.

The judgment makes clear: a judge of one court cannot issue writs against another judge of the same court. This prevents misuse of jurisdiction and protects judges from interference, both external and internal.

Article 199(5) of the Constitution grants this immunity to Supreme Court and High Court judges for acts performed in their judicial and administrative capacity. Without such protection, judges might face pressure or retaliation from colleagues.

If a judge cannot issue a writ against a fellow judge, how can the Islamabad High Court hear a quo warranto petition against Justice Jahangiri? Isn’t that exactly what the Supreme Court said was impermissible?

Article 209 and the Alternative Path

The Constitution already provides a mechanism for dealing with problematic judges. Article 209 establishes the Supreme Judicial Council, which investigates allegations of misconduct or incapacity against superior court judges.

Critics of the quo warranto petition argue that allowing it makes Article 209 redundant. If courts can remove judges through quo warranto proceedings, what’s the point of having a specialized body designed for judicial accountability?

The Supreme Court’s recent judgment reinforced this view, stating that misconduct allegations against judges can only be investigated by the Supreme Judicial Council. But supporters of the petition draw a distinction—they argue quo warranto addresses eligibility before appointment, while Article 209 deals with conduct after appointment.

Political Currents Beneath Legal Arguments

Legal debates rarely happen in a vacuum. Pakistan’s judiciary has undergone significant changes since the 27th Constitutional Amendment. The balance of power between the executive, the parliament, and the judiciary has shifted.

Legal observers note that the executive now enjoys greater influence over judicial affairs. Some suggest judges not aligned with government preferences face pressure from within their own institutional structure.

The timing raises questions, too. Pakistan’s courts handled qualification issues for decades without applying quo warranto to judges. Why now? What changed to make this particular case different?

What Monday’s Hearing Might Reveal

When the Islamabad High Court convenes on Monday to hear this petition, several outcomes are possible. The bench might decide that judicial immunity prevents them from hearing quo warranto against a sitting judge. They could rule that Article 209 provides the exclusive mechanism for addressing judicial eligibility.

Alternatively, the court might distinguish between pre-appointment qualification issues and post-appointment conduct, allowing the case to proceed. Whatever happens, the decision will set an important precedent.

If quo warranto petitions against sitting judges are found maintainable, expect more such cases. If the court dismisses on immunity grounds, it reinforces judicial protection but leaves questions about fundamentally ineligible appointments.

The Bigger Questions About Accountability

This case forces uncomfortable questions about balancing judicial independence with accountability. Judges need protection from interference to decide cases impartially. But judges must also meet constitutional standards and maintain public trust.

When a judge allegedly holds an invalid degree, who should investigate? Bar councils check credentials before licensing, but should they review sitting judges years after appointment? The Supreme Judicial Council addresses misconduct, but does that include misrepresented qualifications?

Courts exercise quo warranto against executive officials and elected representatives—should that power extend to judges? If not, have we created a class immune from accountability mechanisms that apply to others?

What This Means for Pakistani Law

Regardless of Monday’s outcome, this case has already changed something. It’s opened a conversation about judicial immunity, quo warranto jurisdiction, and the Supreme Judicial Council’s role.

For years, courts wielded quo warranto against politicians while judges remained insulated from similar scrutiny. Now that the tool is being tested against the judiciary itself, forcing everyone to think more carefully about its proper scope.

The precedent set here will shape Pakistani judicial practice for years. Young lawyers will study it. Future petitioners will cite it. That’s why this hearing matters far beyond one judge’s situation.

Beyond the Legal Arguments

Lost in legal analysis is a human being whose career hangs in the balance. Justice Jahangiri has served on the bench, decided cases, and built a professional life. Now he must defend his basic qualifications before colleagues.

Whatever the merits of the allegations, this process takes a toll. The scrutiny is intense. The stakes are career-ending. And the questions being asked challenge not just credentials but professional legitimacy built over the years.

The Path Forward

Pakistan’s legal system is at a crossroads. This case will determine whether courts can turn their accountability tools inward or whether judicial immunity creates a protected class beyond such scrutiny.

The answer matters for more than legal theory. It shapes public trust in courts, influences how judges behave, and defines the boundaries of judicial power. Get it wrong, and Pakistan either undermines judicial independence or allows unqualified judges to decide cases affecting millions.

Monday’s hearing won’t resolve all these questions, but it will provide clarity on at least one crucial issue whether quo warranto jurisdiction extends to sitting high court judges. From there, Pakistan’s legal community can chart a course forward that balances independence with accountability, protection with standards, and institutional strength with public trust.